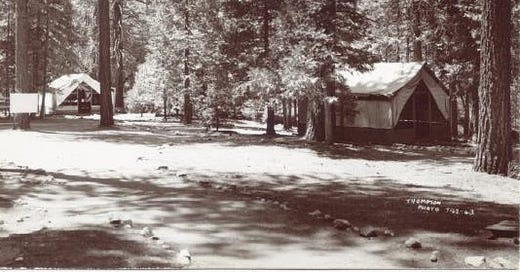

I was lucky enough to go to summer camp from about age 9 to 15. Camp Wasewagan, a Camp Fire Girl Camp in the San Bernardino National Forest was about a three-hour bus ride from my home. The beauty of summer camp was immersion in nature—right outside the tent cabin door—teaching me a form of attentive learning that felt like listening with all my senses.

The whole camp smelled like pine and vanilla

Those weeks in the woods connected me to the natural world in ways that would shape my relationship with trees for a lifetime. The camp was in a forest dominated by Ponderosa Pines. This was the first tree that I learned by name. I associated it with a favorite TV show "Bonanza" where the Cartwright boys ran the Ponderosa Ranch.

The most memorable trait of the Ponderosa Pine is that the bark smells like vanilla— real vanilla— I first thought this was where vanilla came from. The bark sheds puzzle shaped pieces and each is a different shade of polished brown like color chips at a paint store—dark chocolate, cinnamon, caramel— making it useful in all kinds of camp crafts.

The whole camp smelled like pine and vanilla, those summer weeks are favorite childhood memories. I also learned the name of the Manzanita shrub and its smooth red bark that shines in the rain, what poison oak looked like, and I learned that the nettles by the creek burned like a bee sting but it didn't last long and the creek's cool water helped.

Those summertime camp years led to a lifetime of hiking and backpacking. Though I continued to want to identify the trees and plants around me and know their names, nothing was ever as easy as Ponderosa Pine. I struggled with the identifiers—short or long needles—shapes of leaves and flowers, color and scent can only take you so far in plant identification.

During the last 15 years I have become more botanically educated and have begun to understand the significance of taxonomy, how diversely plants have adapted to change and that influences the identifiers. Similarly, increased knowledge of botany changed an enjoyment of gardening into a relationship.

“How amazing is that, within inches below the palm of my hand.”

Trees have long been a main attraction, you can come up close, 'face to face' with the trunk of a tree. Most trees discard their lower branches and widen the crown reaching more and more sunlight, that battle for light is basic and essential for life on earth. I like to place my hand on a tree's cool bark and reflect on how alive it is in its stillness, sheltered by the canopy.

More awareness and botanical knowledge has only deepened my wonder. Now when I place my palm against the bark I can almost feel a pulse, knowing that the heart of a tree is not in its dense 'heartwood' but just below the hardened surface, in the inner soft bark. Here living cells transport sap, which is water carrying sugars manufactured in the leaves from sunlight and air, throughout the tree and roots. A complementary system creates pipelines of cells that carry water and nutrients from the roots up through the tree and strengthen the woody center of the tree that supports its height. How amazing is that, within inches below the palm of my hand.

So many different barks, smooth, rough, flakey-- like a skin the bark protects the tree from disease and insects with compounds produced within the bark. Many trees, like redwoods, have thick, fire-resistant bark that helps them to survive wildfires. The puzzle shapes of the Ponderosa Pine and similar loosening shapes and sheets of bark peel away from trees carrying away infection and parasites.

Barks provide spices like cinnamon and medicinal compounds:

Quinine (from cinchona bark) improved malaria treatment;

Salicylic acid, the precursor to aspirin is in willow bark;

Taxol a important cancer drug came from Pacific yew bark.

Tannins from tree bark have been used to tan leather for millennia. The cork oak has a very thick bark that can be harvested without harm to the tree and it regrows to create a renewable resource.

Look, touch, smell, listen.

The scent of tree barks, like my Ponderosa Pines create environments that many cultures find restorative and calming—something I first experienced as a young camper without understanding the science behind why those vanilla-scented woods felt so comforting.

Even with the increasing knowledge of botanical science there will always still be a mystery to trees and the bark at the heart of their life system. The nine-year-old girl who first pressed her nose and hands against puzzle-piece bark at Camp Wasewagan couldn't have explained the complex biological systems at work, but she understood something essential: trees have a presence in our lives worth noticing.

Today, when I place my palm against the rough texture of a tree trunk—whether in a national forest or my backyard—I'm reconnected to that girl at summer camp who was just beginning to learn the language of the natural world. Look, touch, smell, listen. The Ponderosa taught me my first tree name; all the trees since have taught me that wonder and knowledge aren't opposing forces but companions on the same path.

Trees are just so, so beautiful—a truth I've known since those summer days when vanilla-scented bark first surprised and amazed me.

Who knew bark could smell like vanilla? Your love of trees is infectious.

Love this, Leslie! I loved climbing trees and still do, falling out of my first at age eight. Landing on my back, I couldn't breathe. The neighbor's collie distracted me until I forgot I was dying :) Around the same age I learned while camping the name of my new favorite tree. The scent of eucalyptus, the sunrise call of the loon, it was intoxicating. Admiring your renegade sunflower :)